Just like a small nail in a tire can sideline several tons of powerful steel, a problem with one of the smallest parts of the canine athlete – the toe – can put the brakes on a training session or serious play time.

Just like a small nail in a tire can sideline several tons of powerful steel, a problem with one of the smallest parts of the canine athlete – the toe – can put the brakes on a training session or serious play time.

“Must be a toe” is a common thought when a dog comes up lame. But I must confess that toe injuries are actually less common for most of the dogs I see. The likelihood is that common toe problems, such as a lodged foreign body, are handled simply enough by the owner and never brought to my attention. However, it is quite true that a bum toe can have a significant negative impact on an active dog since our dogs run primarily on their toes.

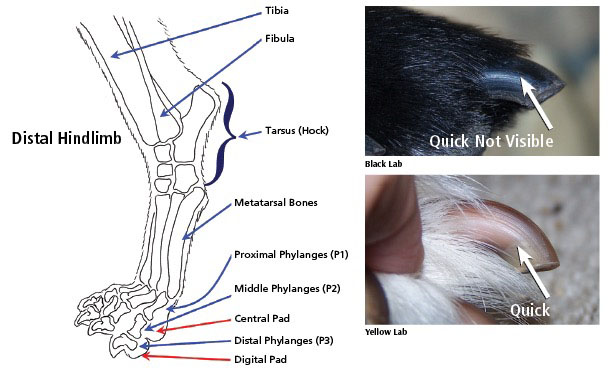

The toe contains many components. Each digit is made up of three small bones known as phalanges. The last phalange is primarily composed of the quick of the toe nail and is termed “P3.” From there, the naming and numbering proceeds up the limb: P2 and P1. P1 articulates with either a metacarpal (forelimb) or metatarsal (hind limb) bone, which connects them to the rest of the limb. This means that each “toe” can be said to contain four bones along with their three joints and associated supporting ligaments and structures.

Anatomically speaking, a dog’s impact surface is nearly 100 percent on their toes. When at a walk or slow trot, the dog will bear all of their body weight on their toes, with more than half of that weight on the forepaws. When running, the feet will hit the ground a little farther up the limb so that the impact is shared with the metacarpal and metatarsal bones. Of course, the toes and meta-bones have cushions to help this impact – pads.

Pads are really not technically part of the toes, but they can be a significant source of pain and lameness if injured. The pads are located under the toe bones approximately at the joint of P3 and P2; the central pad is larger and covers all of the first toe bone (P1) as well as some of P2 and, at times, the ends of the meta-bones covering the joints of all four toes.

Pad injuries are common and can be momentous in terms of causing downtime. Due to the nature of the tissue and their being under constant force, they can be slow to heal. Typically, specialized bandaging is necessary for severe wounds with significant tissue loss or deep lacerations.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]nother common area of injury is the nail. The quick of the nail is actually an extension of the last toe bone (P3). This part of the bone is covered by specialized skin tissue known as “horn” and is equivalent to your fingernail or toenails. Typically, the length and size of the nails are determined and maintained by wear incurred during exercise. For dogs that are kenneled and run on hard surfaces, this is usually maintained naturally. For dogs that stay on soft or smooth surfaces, the nails may not be worn adequately and thus can grow much too long – and they are more likely to be broken.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]nother common area of injury is the nail. The quick of the nail is actually an extension of the last toe bone (P3). This part of the bone is covered by specialized skin tissue known as “horn” and is equivalent to your fingernail or toenails. Typically, the length and size of the nails are determined and maintained by wear incurred during exercise. For dogs that are kenneled and run on hard surfaces, this is usually maintained naturally. For dogs that stay on soft or smooth surfaces, the nails may not be worn adequately and thus can grow much too long – and they are more likely to be broken.

A broken nail is not the end of the world but can be very painful, especially if it is one of the two central nails (which bear a bit more weight than the outer toes). The nails have a copious blood supply and will bleed profusely, as I’m sure you’re aware. Even so, if the dog is quieted and kept relatively still, this bleeding will usually stop on its own. The treatment for a broken nail is usually to simply cut the nail above the break, cauterize the quick to control bleeding, and/or either rest the dog or protect the area with a bandage or boot.

Another common problem affecting toenails and that can cause “toe pain” is a nail bed infection. These infections are typically deep and cause significant redness, swelling, and discomfort of the toe along the junction of the nail and the haired skin. Antibiotics and anti-inflammatory treatments are the usual treatment.

Fracture of the toe bones is another injury. These can be rather troublesome to diagnose unless the veterinarian has good quality X-ray equipment. With a clear film, toe fractures are just like any other bone fracture to diagnose and plan a repair. The repair can vary from doing nothing except resting the dog, to applying small bone plates to stabilize the fracture. The main considerations are the speed of recovery required, the value placed on the dog’s future athletic performance, and the actual degree and type of fracture involved.

Fractures that are not surgically stabilized will take much longer to heal, and if the dog is not adequately restrained (a combination of kennel rest, splints, etc.), the fracture may not heal and result in a non-union. A non-union is a situation in which the fracture does not fuse back together but instead simply forms scar tissue between the break. These usually result in a source of constant pain. The impact this has on a dog’s performance will vary with the temperament of the dog, but will usually result in reduced stamina.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ometimes toe injuries will not break the bone but instead will tear or strain a ligament. Each toe joint has a variety of ligaments, such as the collateral ligaments, as well as other ligamentous structures through which run tendons, not to mention the insertion of the digital flexor and extensor tendons themselves. These structures are all considered soft-tissue structures and heal differently than bony structures. Soft-tissue injuries can be just as painful as fractured bones and may take much longer to heal. For complete healing, the area is required to be rested for several weeks or months. Evidence of soft-tissue injuries can sometimes be seen on radiographs, but the structures themselves cannot, making other imaging methods (like MRI) the only definitive way to diagnose many of these type injuries.

Sesamoids are small bones embedded in tendons that need to cross protruding areas such as joints. The most well-known sesamoid bone is the knee cap (patella). The dog’s foot contains several of these sesamoid bones found within the digital tendons associated with the toes. Over time, within the context of some athletic sports, these sesamoid bones can become aggravated. This inflammation is referred to as sesamoiditis and can be fairly painful. Diagnosis might be made if changes to the bones are noticeable on radiographs, but many times such changes are hard to detect and diagnosis is done through exam findings and the dog’s response to therapy. Treatments vary but usually are centered on anti-inflammatory medications with varying modes of application (injection, topical, oral, etc.).

Lastly, other less common problems that can affect toes are cancers and bone cysts. These problems are typically handled by amputation of the affected toe. Depending on the extent of the problem, the affected toe can be disarticulated at any one of the joints as necessary. When handled properly, the foot can regain function very quickly. In these cases, there will be an unavoidable change in the weight bearing and force loading of the limb. This will put new and unusual stress and torque on joints and ligaments farther up the limb, such as the cruciate ligament in the case of the hind limb. Because of this, special care and attention should be given at the first sign of any soreness or lameness that may indicate the limb is being overworked so that another more serious injury may be avoided.![]()