by Paula Piatt

Does your Lab smile? Grin? Smirk?

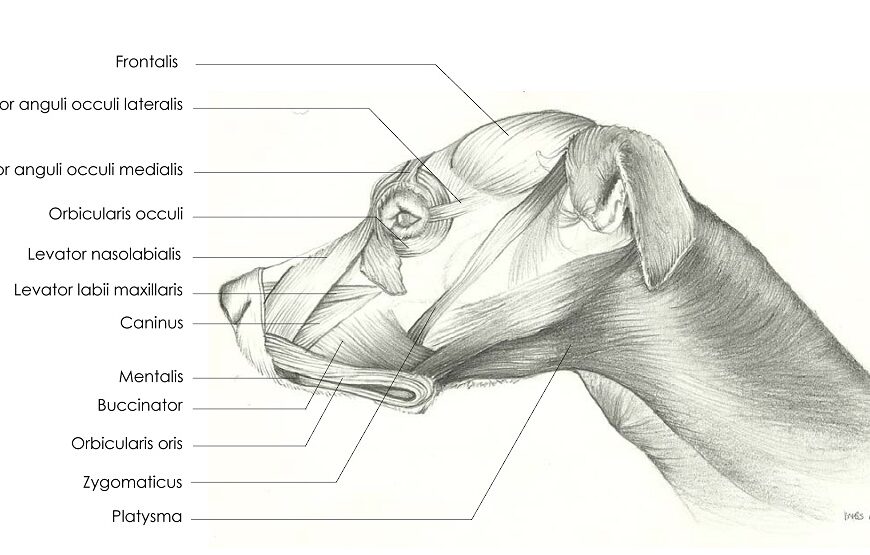

What if I told you he’s simply using his zygomaticus muscle to pull the corners of his lips toward his ears and maybe moving the connected platysma muscle just a little bit? A toothy grin? He’s just channeling his masseter, temporalis, pterygoid, and digastricus muscles.

It’s not nearly as much fun, is it?

Don’t worry, it’s not something the average dog owner will ever need to know. But if you’re a scientist hoping to unlock the mystery of cognitive behavior, cataloging those muscle movements with the Dog Facial Action Coding System (FACS) is a watershed moment for your research.

“Prior to developing this, when we were studying animal face expressions, we were just going on our gut instinct as to what that facial movement meant,” said Dr. Anne Burrows, a professor in the Duquesne University Department of Physical Therapy and the Anna Rangos Rizakus Endowed Chair for Health Sciences and Ethics. “And people from different cultures and ages might interpret that differently. So FACS is an objective measurement system based in the musculature; it doesn’t assign an emotion to a facial movement, it just describes a facial movement.”

With FACS, researchers can now put those facial movements into context.

“Once someone is certified in FACS, they can look at video footage of animals making facial expressions and put the facial movements in the context of what’s going on around them. It’s a way to tap into how animals use facial expression, usually in a social context,” said Dr. Burrows. According to theory, scientists expect animals that live in large social groups to use a lot of facial expression, which takes a lot of thought.

“Whether it’s fair or not, we sometimes equate cognition in animals with how social they are. Fundamentally, FACS is a way for us to tap into how animals think.”

The original human FACS was developed in the late 1970s and quickly moved into the animal kingdom with adaptations for primates – common chimpanzees, rhesus macaques, gibbons, and orangutans. The first research to step away from primates involved the dog in 2013 and has since evolved to include cats, horses, and marmosets. (Information about the entire FACS system is available at www.animalfacs.com.)

Dr. Burrows, a biological anthropologist, was one of several researchers to take on the “mapping” of the dog to help researchers better understand what was going on “inside.”

“We can’t really learn about their cognition or their way of relating to others, so understanding how animals use facial expression is one of the few ways we have to tap into cognition and how they behave socially,” she said.

After identifying a dozen muscles in the face, Dr. Burrows and others then went on to describe the actions of the facial muscles as well as movements in the ear, the head, and the body as a whole, as well as things like sniffing and vocalizations. The smaller muscle movements are discreet and can usually be cataloged only after painstaking review of video. Scientists describe not only the muscle movement, but the appearance changes they cause.

“Let’s say a dog snarls, there’s movement of the lip involved, there’s movement of the nose. So each section of the face that moves gets its own action unit,” says Dr. Burrows, adding FACS practitioners don’t talk about a “snarl,” as they document particular movements. For them, it’s important to remove the emotion from the situation.

Dr. Burrows knows the average dog owner can’t do that, whether it’s reading action units or disregarding emotion. You’re just sitting at home on the couch, laughing at that big, toothy grin from your goofy Lab. You may know, from years of experience, that he’s smiling and happy and generally enjoying life.

Misunderstanding a dog’s body and facial language, however, can lead to tragic results. Children, for example, will often interpret seeing the teeth of the dog as a smile, even if the dog is growling.

“You see this all the time on social media where parents have their infant playing with a dog and, clearly, the dog doesn’t like what’s happening,” said Dr. Burrows who, after years of study can read that dog’s expressions. “Being able to recognize when your dog has had enough of your baby pounding on its face, and that dog is about to bite, that’s really important.”

Dr. Juliane Kaminsky, a comparative psychologist at the University of Portsmouth in England and one of the original DogFACS contributors, says researchers are getting closer to bridging the context gap of facial expressions and what they mean, although it’s a slow process. They are currently working on a catalog of sorts – an objective collection of a dog’s facial movements.

“Very often what we see is a very subjective description of facial movements in dogs. We see pictures and then there is a description that this dog is ‘fearful,’ or this dog is ‘angry.’ They are all subjective interpretations of what is actually going on in the dog’s face,” she said. “I’m not saying that we are wrong in our interpretations, but from my perspective as a researcher, I think we have, potentially, definitely skipped a step and might have gone in the wrong direction in some areas.”

Because there is currently no objective research when it comes to facial expressions of dogs, Dr. Kaminsky thinks we may have settled to think that we really understand what dogs’ facial expressions mean.

“If there are facial movements that always happen in contexts where the dog seems to be scared or might have a negative reaction, then I have no problem to call that a fearful expression. But we haven’t gotten there yet,” Dr. Kaminsky says. “I think what we are missing is an objective ethogram [or catalog of behaviors] of dog facial movements. We are working on that; it’s a very time-consuming process.”

The latest development is NetFACS, a statistically meaningful way to analyze data collected through FACS by taking the movements and plotting them around seven expressions (anger, fear, surprise, sadness, contempt, happy, disgust). They can discover which muscle movements are common to each expression and how they work together.

Both Dr. Kaminsky and Dr. Burrows hope eventually to give dog owners the ability to look at their dog’s face and know what they are thinking. Until then? Take the time to enjoy your Lab, get to know his unique expressions and quirks, and appreciate his wonderfully active zygomaticus muscle.

Featured image: Illustration used with permission, DogFACS Manual (Image by Inês Martins; Evans 199