Human cardiac surgery heals Labs.

by Debbie DeRoma

Emma Hancock feared her passenger’s ailing heart might give out before they reached their destination. She rested her arm across his furry chest, relieved to feel the steady cadence of his breathing. He was sedated when Hancock sprung him from the ER earlier that day, absconding with him despite his fragile condition. As the wooziness wore off, she slipped him painkillers, hoping to keep him comfortable and blissfully unaware of the peril he faced.

Hancock’s journey to Cincinnati began several months earlier in a Toronto dog park. Unlike the lively Labradors she previously owned, five-month-old Bear was a placid pup who loved to lounge. “I’m thinking I’ve just struck gold because I’ve got this really laid-back Lab,” she says.

But Hancock’s dogwalker suspected Bear’s lethargy signaled something more serious. He struggled to keep pace with the pack during group walks and seemed reluctant to roughhouse with other dogs in the park. “She said she’d never seen such a docile Lab, especially for his age,” says Hancock.

When her veterinarian blamed Bear’s behavior on growing pains, Hancock thought he was in the clear. But her relief turned to trepidation later that night. “I had my hand on his chest, and I did a double-take,” she says. “I thought, that can’t possibly be his heart rate.”

Bear’s pulse was racing so fast Hancock couldn’t count the beats. She rushed to the animal hospital, but his heart rate returned to normal by the time the technician took his vitals.

A flurry of vet visits followed before a fortuitous encounter with a canine cardiologist yielded a diagnosis. Bear had an arrhythmia, the medical term for an abnormality with the heart’s rate or rhythm. Bear’s heart rate was too high, a condition called tachycardia, and his prognosis was dire.

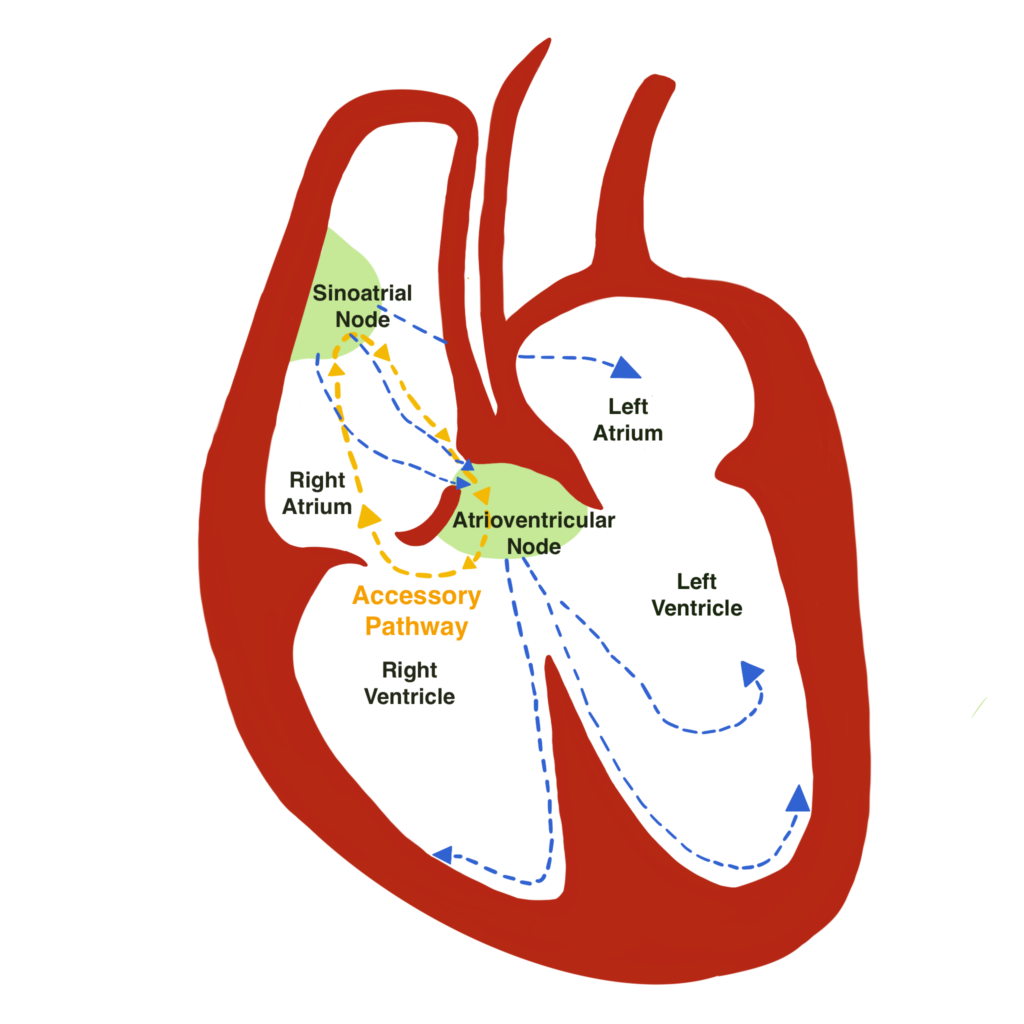

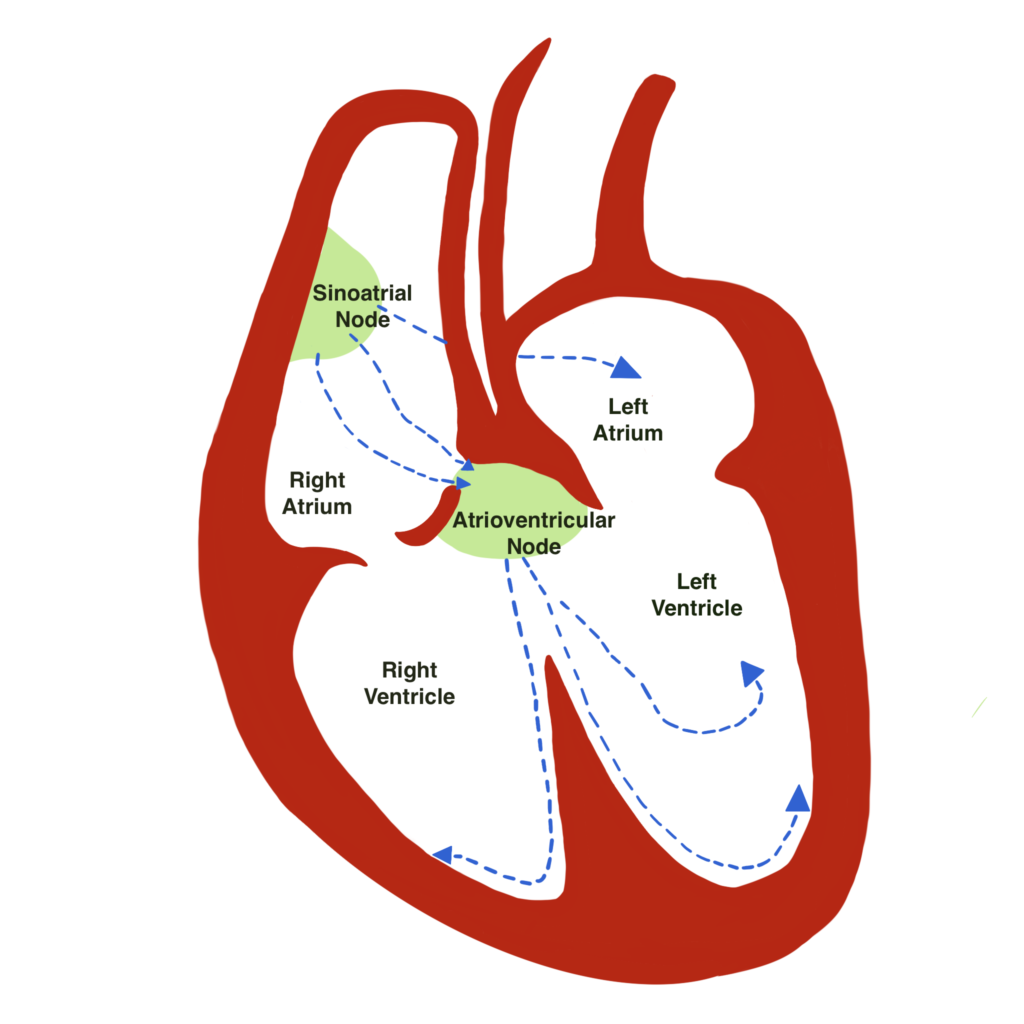

Like humans, a dog’s heart has four chambers – two upper chambers called atria and two lower chambers called ventricles. The heart’s electrical system regulates pumping and sets the heart rate and rhythm.

The sinoatrial node – an area of specialized tissue near the top of the right atrium – initiates an electrical impulse, causing the atria to contract and pump blood into the ventricles. The impulse then travels to the atrioventricular node, which acts like a gate and delays the impulse long enough for the ventricles to fill completely with blood. The impulse then causes the ventricles to contract and send blood to the lungs and body. This process repeats with every heartbeat.

In a healthy heart, impulses only travel along a single electrical pathway regulated by the sinoatrial node. However, some dogs are born with extra electrical connections between the atria and ventricles that short circuit the usual electrical pathway, causing tachycardia.

A dog’s normal heart rate ranges between 60 and 140 beats per minute. Dogs with tachycardia may experience heart rates exceeding 300 beats per minute. When the heart beats too fast, the pumping chambers can’t adequately fill with blood, meaning less blood is sent to the body’s tissues. Sustained tachycardia can lead to deterioration of the heart muscle, congestive heart failure, or sudden death.

Unfortunately, tachycardia can be difficult to detect. Some dogs exhibit no outward signs, while others may appear fatigued or dizzy. Other symptoms include gastrointestinal distress, lack of appetite, vomiting, and rapid panting. Because these symptoms mimic those of other illnesses, owners, and even experienced veterinarians, sometimes overlook these critical clues to heart rhythm problems.

It took nearly a year for Tracy Dykens’ Lab, Suki, to be diagnosed. Like Hancock, Dykens assumed Suki was just a mellow Lab. “This was my first dog,” she says. “And I thought I was the best puppy trainer ever because she was so easy.”

At 11 months old, Suki began drooling and looked lethargic. Blood tests and X-rays appeared normal, so Dykens’ veterinarian attributed Suki’s symptoms to nausea and food intolerance. For months, Dykens consulted nutritionists and tried different diets. Nothing helped. The once voracious eater now barely touched her food. Her weight dwindled to 40 pounds. “She was wasting away,” says Dykens.

One day, as Dykens rested her head on Suki’s chest, she noticed Suki’s racing pulse. “I could just feel her whole body shaking from it,” she says.

After fitting Suki with a heart monitor, doctors diagnosed her with a type of tachycardia caused by an accessory pathway – an extra electrical connection between the heart’s upper and lower chambers. They also told Dykens about radiofrequency catheter ablation, a surgical technique that could save Suki’s life.

There was just one problem. Dr. Kathy Wright, the canine cardiologist trained in ablation surgery, was in Cincinnati, Ohio – more than 2,600 miles from Dykens’ British Columbia town. Undeterred, Dykens and her husband hit the road with Suki the next day.

Bear’s diagnosis didn’t take as long as Suki’s, but his journey was no less harrowing. Frightened and frustrated when repeated vet visits proved inconclusive, Hancock finally caught a lucky break when she took Bear to an emergency clinic. By chance, a canine cardiologist was on staff that night, and after diagnosing Bear’s accessory pathway tachycardia, she urged Hancock to contact Dr. Wright immediately.

With Bear’s surgery only four weeks away, his condition deteriorated. “He would just appear to be overcome with exhaustion and drop to the ground,” says Hancock.

When he was hospitalized for the third time a few days before his surgery, Hancock couldn’t wait any longer. She sprung Bear from the emergency clinic and drove to Cincinnati early, praying he would survive long enough for Dr. Wright to operate.

Dr. Wright’s own heartbreak prompted her to pursue veterinary cardiology. Her childhood dog Princess died of congestive heart failure, and Dr. Wright vowed to help other dogs with this disease.

One of Dr. Wright’s first patients was a Labrador puppy suffering from tachycardia and congestive heart failure. The antiarrhythmic drugs she prescribed became less effective over time, and she struggled to manage his condition long-term.

Having completed a post-residency at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Dr. Wright knew radiofrequency catheter ablation could cure tachycardia in children. So, she recruited her pediatric colleagues to help adapt the technique for dogs.

Cardiac catheter ablation uses radiofrequency energy to destroy the small area of the heart tissue causing rapid or irregular heart rates. Tiny flexible wires, called catheters, are threaded through large veins in the neck and groin and positioned at key locations within the heart. The catheters are hooked to a stimulator that delivers an electrical impulse and records the heart’s electrical activity. Dr. Wright uses this information to create an electrical roadmap and locate the cells producing the abnormal rate. Once the heart is mapped, an ablation catheter destroys the abnormal cells using radiofrequency energy (similar to a microwave), allowing the heart to resume a normal rate. “It essentially cauterizes that little area in the heart,” says Dr. Wright.

Most dogs Dr. Wright treats have accessory pathway tachycardia. Accessory pathways are one of the most common causes of rapid heart rates in young dogs, but they are tricky to diagnose and often get overlooked. “Many of these young dogs present with gastrointestinal signs,” says Dr. Wright, “which may take veterinarians down the trail of a gastrointestinal foreign body or dietary indiscretion, rather than pursuing heart rhythm as a cause.”

Labradors seem especially prone to accessory pathway tachycardia. The breed accounted for nearly half the patients in Dr. Wright’s 2018 study in the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, and she’s investigating possible genetic links.

Dr. Wright is one of only two veterinarians in North America to perform canine cardiac ablations. The difficult procedure requires specialized equipment too expensive for most animal hospitals, but Dr. Wright is seeking donations to reduce the costs. “My hope is to partner with additional electrophysiology equipment companies to help us further advance treatment and make this available to more pets,” she says.

So far, Dr. Wright and her team have performed ablations on 159 dogs with accessory pathway tachycardia, and their success rate exceeds 97 percent. Unlike antiarrhythmic medications, which require monitoring and often lose effectiveness, the minimally invasive surgery is an immediate, lifelong cure. Owners are often surprised by the sudden changes in their dogs’ energy levels.

Hancock could barely believe how quickly her once docile dog became an exuberant Lab. Bear suddenly loved running, swimming, and chasing his ball. “He was all systems go at that point,” she says.

Suki’s transformation was equally impressive. She gained back all the weight, and Dykens calls her a “full retriever” now. “She will play fetch until she drops.”

Hancock and Dykens hope their stories raise awareness of ablation surgery. They urge Lab owners to check their dogs’ pulse rates, particularly if their pups seem lethargic. Owners who suspect their dogs have accessory pathway tachycardia can ask their veterinarian to refer them to a cardiologist, or contact Dr. Wright’s office at cincy.cardio@medvet.com.

Sadly, Bear developed an aggressive form of leukemia and passed in December 2022. But Hancock ensures his legacy lives on by sharing Bear’s journey through videos and testimonials. “I personally believe his purpose on this earth was to go through this, connect us with Kathy, and spread the word and save other dogs like him.”

For more information about the study, visit onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/jvim.15248.

This article originally ran in the May/June 2024 issue of Just Labs. You can purchase this individual issue or choose to subscribe to our publication through our online store.